Welcome to a special Omakase Formula post! While this is still a post related to F1, it’s something a bit different from my regular race recaps and end-of-season RACES and awards posts. It’s also a bit different because, for the first time ever, you can listen to an Omakase Formula post! This is something I’m trying out, and I won’t guarantee you’ll see this often. Or even at all, if it turns out everyone hates hearing my voice. I’m only assuming that’s not the case because we’ve done eight podcast episodes so far and no one has complained yet. The comments section will still remain open for you to do so though!

Before you read this post, be sure to also check out my post about the 2025 Monaco Grand Prix if you haven’t yet. That piece will discuss things specific to this year’s race that I won’t cover in detail here. And if you’re waiting for my recap of this past weekend’s race in Spain, fear not: that post is still coming later this week.

With that, let’s begin.

The Monaco Grand Prix—one of the three races that make up the “Triple Crown” of motorsports—is a spectacle. It’s easy to see why this race is considered F1’s “crown jewel.” After all, the image F1 has successfully curated for itself over the years—one of speed and sophistication—is almost entirely courtesy of the Monaco Grand Prix and its timeless images of cars zooming by yachts along the Mediterranean.

But there’s a reason why “spectacle,” and not another term like “great race” is used to describe the Monaco Grand Prix. The tight and twisty medieval streets the race takes place on were never made for racing. Three-time world champion Nelson Piquet famously compared driving around Monaco to “riding a bicycle around your living room.” It’s no wonder that overtaking—a barometer most spectators would use to determine whether a race is good or not—has always been difficult around Monaco. And that difficulty has only increased in recent years, with cars getting larger while the Monaco streets stay the same. Racing at Monaco has been described as a “parade,” and this year’s attempt at fixing the issue turned out about as well playing stupid games and expecting to hit a billion dollar jackpot. Unsurprisingly, a lot of the conversation post-Monaco revolved around whether F1 has outgrown Monaco, with many online arguing that perhaps it was time to leave the race in the past. Others stuck to a more neutral or indifferent tone. Sure, removing Monaco would be severing a major historical link, a tragedy given the sport’s seemingly gradual ignorance of its own past as it chases global expansion and a newer audience. But would replacing the race for one that could provide more racing excitement hurt? No.

I, however, am a Monaco defender. That’s not to say I think Monaco is perfect. But I also think a lot of complaints about Monaco miss the forest for the trees. Criticism surrounding the race—and the track specifically—tends to view Monaco as the problem. But I would argue that Monaco is actually an extreme symptom of some of the issues plaguing F1 today.

I’ll admit Monaco is extremely easy to hate. If it feels like F1 bends over backwards just to race in Monaco, that’s because it does. F1 has always raced here, even though it arguably never should have. The track has always been too narrow and there’s always been a lack of runoff. If Monaco were proposed today as a new race, there’s no way it would ever be approved. And if you think Monaco’s hanging on to a spot on the calendar because it’s paying an exorbitant sum to host the race, think again: estimates say Monaco now pays about $32 million per year to host the Grand Prix. It’s a significant increase from the estimated $20 million it used to pay, but it’s still one of the lowest hosting fees on the calendar. For comparison, the likes of Azerbaijan, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia pay over $50 million per year.

So why does Monaco have a hold over F1? Location is definitely a part of it. Monaco’s reputation as a glamorous playground for the rich and famous has always meant the Grand Prix has attracted a celebrity crowd so extensive it’s every paparazzo’s wet dream come true. And even though F1 now relies more on Netflix than celebrities to advertise the sport, no other F1 track looks quite as good on screen as Monaco:

It’s not as if F1 hasn’t tried to replace Monaco. I would argue the Miami Grand Prix was deliberately set up by Liberty Media (the American company that currently owns the group of companies responsible for F1) not only to tap into the American market but also to steal Monaco’s crown as the flashy F1 race you have to attend. The results speak for themselves:

Yes, those are real boats on fake water. The desperation is tragicomic. No one is fooled. If it looks like a parking lot and quacks like a parking lot, it is a parking lot.

Another argument for why F1 might have a soft spot for Monaco is its historic nature. Only one racetrack has hosted more F1 Grands Prix than the Circuit de Monaco. As a result, you’ll notice as this post goes on that the track is steeped in F1 lore. But while you could make the argument that Monaco should be kept because of its history, I won’t actually be making that argument in this post. Preserving something historic for the sake of history is great if we’re talking about a museum. But F1 is not a museum, and keeping Monaco on the calendar while the sport evolves simply because there’s always been a race there would eventually run the risk of making Monaco look as out of place as King Tut’s mask in a McDonald’s.

In fact, that’s basically the argument people are now making for removing Monaco: F1 has evolved and made the event look awkward compared to the rest of the season. But that doesn’t make sense because, as I said earlier, Monaco has always been an outlier. It stood out as awkwardly in 1950 as it does today—like a sore thumb or a polar bear in Arlington, Texas. Or, since this is Monaco we’re talking about, like a polar bear at the poker table. At first glance, you think, “What the hell is it doing here?" and immediately assume it’s bluffing its way through. But you don’t need to be a poker pro to know you can only bluff for so long before you’re exposed for having nothing. If the Monaco Grand Prix truly wasn’t any good, F1 would’ve found a way to get rid of it a long time ago.

So why does this race still exist?

Turns out, Monaco is a polar bear with pocket aces—those aces being the Circuit de Monaco itself. The track holds the key to why Monaco doesn’t just have a seat at the table, but dominates as the chips leader. At 3.337 km (2.074 mi), the street circuit is by far the shortest track on the F1 calendar. Zandvoort, the next shortest track this year, is almost a full kilometer longer. Spa, the longest track of the season, is more than twice as long. But despite its diminutive nature, Monaco has carved out a reputation for being a demanding place to race. The Grand Prix is the only race during the season that doesn’t adhere to the FIA’s mandated 305 km (190 mile) race distance, because reaching that distance on this slow and complicated circuit would cause the race to exceed the two-hour time limit an F1 race can run without red flag interruptions. Size, then—at least in F1—doesn’t matter.

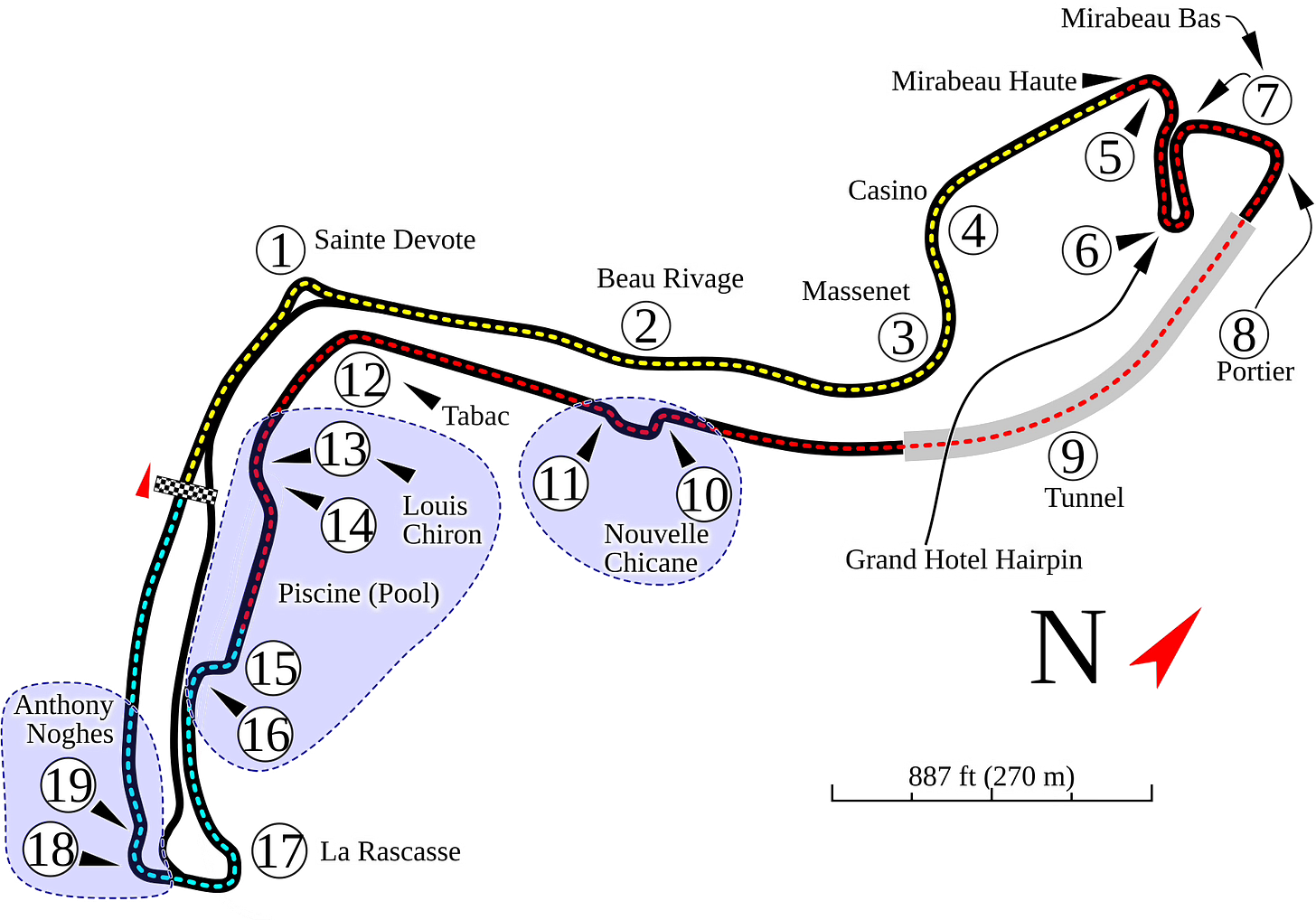

Understanding the Circuit de Monaco itself is key to understanding why the Monaco Grand Prix is so special. Unfortunately, that means you’ll have to bear with me as I spend the next part of this post nerding out over every aspect of this track, from all the challenges it presents to just some of the legendary moments that have taken place on these streets. If you’re listening to the audio of this post, I highly recommend you to pull up the text of this post and follow along for this next part so you can look at the photos while I talk about the track. I’ve also included a diagram of the track at the start of this next section so you know how each corner fits into the overall track.

Turn 1: Saint Dévote

This corner’s name comes from the nearby chapel dedicated to Saint Dévote, the patron saint of Monaco. The corner initially had a mini barrier around the inside to separate the pit lane exit from the track, which made the corner effectively narrower than it already was. This meant a fair share of pileups would occur, such as the three-car crash between David Coulthard, Jean Alesi, and Gerhard Berger in 1995. The barrier was removed in 2003, but accidents still take place in form of a driver locking up into the corner and colliding straight into the wall—Felipe Massa had almost identical accidents here two days in a row in 2013. Pile-ups can still occur though: the 2012 Grand Prix race saw chaos here on the opening lap, and seven cars were taken out at the start of this year’s F2 feeder round!

Turn 2: Beau Rivage

The name is French for “beautiful coastline,” which doesn’t really make any sense given you’re climbing up the hill to the highest part of the circuit at this point of the lap. The real “beau rivage” is still to come in the latter half of the lap when the cars zoom by the harbor. This is another place where collisions occur at the start of races as drivers jostle for position, something which happened in the 2024 race.

Turn 3: Massenet

Named after French opera composer Jules Massenet, who has a commemorative bust located outside the opera house that this long left-hander sweeps by. Though not quite a double-apex corner, you’ll see drivers treat it as such, with cars initially touching the inside kerb and then drifting out, only to cut back in again towards the barrier so that they can get the best entry into the next corner. Overtaking here, while extremely rare even by Monaco standards, has happened before: 2007 world champion Kimi Räikkönen passed Mark Webber on the outside in 2006.

Turn 4: Casino Square

Monaco’s 42 meters (138 feet) of elevation change is one of the largest on the F1 calendar, and cars reach the highest point of the track at this corner. Casino Square may not be as heavily-steeped in F1 lore as other corners of this track, but it doesn’t need to be. The iconic photos speak for themselves.

Turn 5: Mirabeau Haute

Turns 5 and 7 are named after a former hotel located by these corners. The steep, downhill braking zone before Mirabeau Haute is incredibly tricky—especially in the wet. The corner also features two quirks that illustrate the added complexity of racing on public streets. Drivers have to swerve as they drive down to the corner from Casino Square in order to avoid a bump in the road that would unsettle the car. Although less noticeable, the track also falls away on the inside at Mirabeau Haute, meaning drivers have to be careful in order to avoid locking the front wheels under braking.

While overtakes have happened at this corner in the past—see Stefan Bellof in 1984—the most famous moment is undoubtedly Patrick Tambay’s failed overtake in 1986, which saw him collide with Martin Brundle and barrel roll into the barriers.

Turn 6: The Hairpin

Other tracks have hairpin turns, but Monaco’s is undoubtedly the Hairpin. This is the slowest corner on the F1 calendar, with cars going around the turn at just 48 km/h (30 mph). As Gabriel Bortoleto showed this year, overtaking is still possible here. In 1982, Riccardo Patrese lost the race lead when he spun out at this corner—only to win the race in one of the wildest finishes in F1 history when each of the three subsequent cars that inherited the race lead were forced to retire during or before the final lap.

Turn 7: Mirabeau Bas

The lower Mirabeau corner seemingly has a lot of room on the inside, but the rough brick surface there means drivers won’t put more than their right wheels on that portion of the track. In 1996, seven-time world champion Michael Schumacher’s opening lap crash here in the rain arguably kickstarted the most chaotic Grand Prix in F1 history, one that saw only three drivers make it to the finish line.

Turn 8: Portier

Named after a nearby neighborhood, Portier is not a common overtaking spot. However, both Nico Hülkenberg (in 2014) and Kimi Antonelli (this year) showed it’s possible. This corner is immortalized as the place where three-time world champion Ayrton Senna famously crashed out in 1988. Senna had been leading that year’s race by over a minute, but a freak lapse of concentration sent him into the wall and handed victory to four-time world champion Alain Prost, who at the time was Senna’s teammate and championship rival.

Turn 9: The Tunnel

Officially, the tunnel in Monaco is one of two tunnels on the calendar. But I would argue the pit lane underpass at Abu Dhabi shouldn’t be allowed to scam its way next to Monaco’s actual tunnel. Racing through this part of the track presents a unique challenge because of the shift in visibility as cars enter and exit the tunnel. It also provides an interesting logistical issue when there is rain. During the notoriously wet 1984 race, the track surface in the tunnel was purposefully watered down so that conditions matched the parts of the track outside. Conversely, the race start had to be delayed in 1981 after a fire in the hotel above resulted in water from the firefighting efforts leaking into the tunnel.

Turns 10-11: The Nouvelle Chicane

The name here is straightforward: this chicane is “new” because it replaced the old Chicane du Port in 1986. Although Monaco gets a reputation for being a slow circuit, cars still reach 290 km/h (180 mph) as they brake for the Nouvelle Chicane. The braking zone here is challenging, not just because it’s downhill and because of the speed cars are traveling at, but also because the road dips right at the braking point. Sergio Pérez’s crash here during qualifying in 2011 was particularly nasty, but he’s far from the only driver who has been caught out by this part of the track. 2009 world champion Jenson Button and 2016 world champion Nico Rosberg both suffered large crashes here during practice sessions in 2003 and 2011, respectively.

Getting the braking at the Nouvelle Chicane right is also important because this point is considered the main overtaking spot in Monaco. 1992 world champion Nigel Mansell made a famous overtake on Prost at this corner in the 1991 race.

Another interesting thing about the Nouvelle Chicane is that the ideal line through the corner is different from what the track would suggest visually. If you look at the corner, you might think the exit is a right-left sequence. But you’re actually supposed to point the car right at the left-hand barrier that juts out at the exit and get as close as possible to it before gradually straightening the car out once you’re on the run down to the next corner.

Turn 12: Tabac

This corner gets its name from the fact there used to be a tobacco shop here. In 1950, water from the harbor washed up onto the track here and wreaked havoc throughout the race, most notably on the opening lap, when a pile-up effectively took out half the starting grid. In 2004, Takuma Sato’s engine exploded at Tabac, and the ensuing smoke that enveloped the track caused Giancarlo Fisichella to crash into Coulthard and flip over.

Turns 13-16: Louis Chiron and Piscine (The Swimming Pool Section)

Although the term “swimming pool section” refers to this sequence of corners as a collective, only Turns 15 and 16 are called “Piscine”—French for “swimming pool.” Turns 13 and 14 are named after Monegasqué driver Louis Chiron, who holds the record for being the oldest driver to start an F1 race at 55 years and 292 days.

While modern F1 cars have enough grip that drivers don’t have to lift off the gas at Louis Chiron, the same can’t be said for Piscine, which is tighter and presents another risk-reward opportunity for drivers. Getting as close to the barrier as possible on the right-hand turn while going over just enough of the kerb on the subsequent left-hander is key to setting a fast time. Make a mistake, though, and you’ll be lucky if you’re still driving the car towards the next corner. In 2016, four-time world champion Max Verstappen clipped the barrier at the right-hand part of Piscine during qualifying, which sent him over the entire kerb on the left-hander and straight into the barrier. Verstappen would go on to replicate that crash during practice in 2018, and he ended up being unable to participate in qualifying that year because his car couldn’t get repaired in time.

Turn 17: La Rascasse

“Rascasse” is French for scorpionfish, which can be found in the Mediterranean and is an ingredient in Bouillabaisse—a traditional Provençal fish soup. In this case, it also refers to the restaurant that overlooks the corner. As with many other corners on this track, braking at Rascasse is trickier than it initially appears. Because the track curves left leading up to the corner, drivers have to brake while steering, which is incredibly difficult given the lateral load the cars are experiencing here. If that wasn’t complicated enough, drivers then have to turn the car the other direction while still braking in order to navigate Rascasse itself. But despite how difficult Rascasse is, the corner’s most infamous moment involved a driver failing to negotiate it on purpose. In 2006, Schumacher notoriously parked his car here towards the end of qualifying in order to bring out the yellow flags and prevent two-time world champion Fernando Alonso, Schumacher’s rival for the championship that year, from out-qualifying him.

Turns 18-19: Anthony Noghès

Named after the founder of the Monaco Grand Prix, this corner is one of the few spots on the track where cars can drive comfortably side-by-side. Its most famous incident features Schumacher and Alonso once more. In the 2010 Grand Prix, Schumacher passed Alonso here on the last lap as the Safety Car pulled into the pit lane to initially finish the race sixth. However, despite the green restart lights being illuminated when Schumacher made the move, the overtake was ruled illegal post-race because the stewards deemed the race had technically ended under Safety Car conditions. Schumacher was handed a 20-second penalty that dropped him down to twelfth, but the FIA also conceded the rules were unclear and modified the regulations to prevent similar confusion in the future.

So what does all of what I’ve just said look like when put together? The best place to start would be Senna’s legendary qualifying lap from 1988, which saw him go an incredible 1.427 seconds faster than anyone else on the grid. However, that lap was not televised, meaning no footage of it exists. For a more modern visualization that you can actually watch, I recommend Lando Norris’ record-breaking qualifying lap from this year. And although a normal race at Monaco free of any chaos may be a bit dull, the weekend still offers plenty of excitement. Qualifying always delivers (a good one to watch would be 2023), and Saturday at Monaco is consistently more exciting and intense than actual races at plenty of other tracks.

You’ll understand once you watch any lap at Monaco why this is the race every F1 driver wants to win. The track’s sheer difficulty and demand for mistake-free driving means there is no greater technical and mental challenge during the season. So being able to say you’ve won at Monaco? That’s an achievement in F1 that is second only to winning a championship.

That’s the thing about the Monaco Grand Prix: the race might be boring if you look at it as a spectator, but you quickly realize just how fascinating and special the event is when you shift your perspective. The ever-increasing speed of technological advancements can sometimes mean F1 feels increasingly like an engineering championship. Yet Monaco stands tall against that technological wave: it’s a place where winning depends more on man than machine. You might think that’s just a by-product of the modern era, where F1 cars are so large that overtaking on Sunday is nearly impossible, but you’d be wrong. In 1961, Sir Stirling Moss claimed victory against Ferrari in an older, under-powered Lotus. In 1992, Senna famously held off Mansell’s superior Williams in the closing stages. In 2012, Schumacher set the fastest qualifying lap1 in a Mercedes that belonged at best in the middle of the grid. Monaco has always been a place that rewards great driving, and the fact that still holds true today means I would argue it’s actually stood the test of time better than most other F1 circuits.

I know what I just said might be considered scandalous. After all, the conventional view nowadays is that F1 has outgrown Monaco. But how much of that is actually Monaco’s problem? After this year’s Japanese Grand Prix, a race universally panned as being a “parade” (sound familiar?), people immediately questioned whether F1 was becoming a qualifying championship rather than a racing one. The prevailing arguments were that overtaking was becoming extremely difficult because cars were too wide, dirty air had an outsized impact on performance, and tires were too durable. If that was the case—and that was the consensus—then why is it that when those same problems appear at Monaco, the conversation suddenly turns to whether Monaco is unfit for F1?

I’m not saying everything is perfect right now. Monaco amplifies the issues that were brought up after this year’s race at Suzuka, and its status as F1’s “crown jewel” doesn’t make it exempt from change. Alex Wurz, chairman of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association, outlined three possible places where the Circuit de Monaco could be modified to improve overtaking opportunities. Those proposals—widening Rascasse and the Hairpin along with moving the Nouvelle Chicane—are solid starting points that would also be relatively feasible. But even if you dismiss proposals to change either the Circuit de Monaco or the format of the Grand Prix and believe Monaco truly doesn’t belong on the F1 calendar, getting rid of Monaco won’t get rid of F1’s dirty air problem and size problem. Those issues seem easy to ignore now because Monaco exists as a perfect scapegoat. But refusing to fix them and removing Monaco instead only guarantees people will become more aware of the issue at other tracks. Sure, you could keep removing old tracks and replace them with newer ones. But that’s not logistically feasible. Nor is it guaranteed to give you better results. If newer tracks were indeed better for racing, we’d see drivers and fans constantly list them amongst their favorite Grands Prix. Yet it’s still the old guard, tracks like Silverstone, Spa, Suzuka, and yes, Monaco, that continue to dominate the conversation year after year.

Perhaps then, we should stop only thinking of Monaco as the problem and instead also appreciate what it brings to F1. We can discuss how the average Sunday feels processional while still acknowledging F1 rarely comes alive more than it does on Saturdays. Rather than exclusively criticize the track for not offering overtaking opportunities, we can recognize how it offers up the biggest challenge of the year for the drivers. While Monaco is imperfect, we can celebrate how its idiosyncrasies offer something unique to the sport that we won’t see any other race weekend. And at the end of the day, that individuality Monaco possesses is why I believe it’s deserving of a place on the F1 calendar. In an age where it can feel like F1 is becoming increasingly cookie-cutter, there simply isn’t—and nor will there ever be—a race weekend like the Monaco Grand Prix.

If, after reading this, you still believe the only thing that matters when it comes to F1 is the viewing experience on Sunday, I completely respect your decision to continue disliking the Monaco Grand Prix. There are 23 other races in the year, and you are more than welcome to tune in to any of those weekends and opt out of this particular one. And if you find yourself watching the race next year while complaining about it and wondering why you’ve tuned in despite knowing what to expect, maybe that’s a sign you’re just as captivated by the Monaco Grand Prix as the rest of us.

He started the race P6 due to a five-place grid penalty incurred at the previous Grand Prix.